1935

Richard

2019

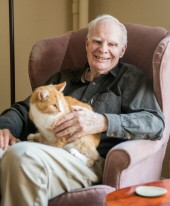

Richard Shaw Wheeler

March 12, 1935 — February 24, 2019

Richard S. Wheeler prolific author, Livingston legend, friend to many died at his home on Sunday, Feb. 24, 2019. Wheeler, who was 83, had been diagnosed with leukemia in late January.Shortly before he died, Wheeler told friend Joseph Bullington that he hadnt been able to write for about a year, couldnt put a sentence together."Well," Bullington responded, "maybe its about time you saved some for the rest of us."Since he took to writing books full time in 1985, Wheeler authored more than 80 titles westerns, novels of historical fiction, even some detective novels. His most loved work includes the Barnaby Skye series, which follows a frontiersman character, and "The Richest Hill on Earth," a historical novel about the Copper Kings of Butte, to name but a very few.His output has not gone unnoticed: The Western Writers of America honored him with six Spur Awards, the 2001 Owen Wister Award for lifetime achievement, and a 2015 induction into its Hall of Fame.Wheeler was born in 1935 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin and was raised in nearby Wauwatosa. He studied history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison but did not take a degree.Friend and renowned writer Tim Cahill, who also studied history at the U of W, said Wheeler was a writer even then."We agreed that we both chose history because its mostly about stories, and we both loved stories," Cahill said.But, Cahill went on, Wheeler didnt slouch on the history part, either."If Richard researched something, then hed really done the research," he said.After trying his hand, very briefly, as a screenwriter in Hollywood, Wheeler started his writing career as a newspaper reporter and worked for a series of newspapers in the 1960s, including the Billings Gazette, where he drove into work each day from a cabin outside of Roundup. He later worked as a cowboy on a ranch in the Arizona borderlands and as an editor for book publishing companies before giving up a steady paycheck and moving to Big Timber, Montana to write novels at the age of 50. He eventually settled in Livingston, which he said became the "literary center of Montana" after many writers moved to the area in the 1970s and brought with them filmmakers, musicians and artists.Scott McMillion, a Livingston writer and the publisher of the Montana Quarterly, praised Wheelers contribution to western literature."Richard did a lot to help people understand the real West, as opposed to the mythic West," said McMillion. "His stories, especially his later stories, are about people making a living and living a real life in the West."Richard would admit that some of his novels were spotty," McMillion continued "but what do you expect when he wrote 80 of them," he added, laughing.When Wheeler began writing a series of detective novels under the pseudonym Axel Brand, friend and songwriter Ben Bullington asked him why he chose that name. Wheeler responded that he was sick of alphabetical order burying his books at the bottom of the shelf."He understood the mass market," said McMillion he understood that when people are looking for something to read from an airport bookshelf, "the Bs do better than the Ws."In 2000, Wheeler married Sue Hart, an English professor at Montana State University-Billings and a longtime friend. The couple kept their own separate houses she in Billings, he in Livingston and spent weekends together."He, I think, craved that quiet time for writing," said his step-daughter Margaret Gilluly-Marquez, "but he was with her through thick and thin."Hart died in 2014.Late in Wheelers life, his friend Bill Payne, musician and former piano player for the band Little Feat, encouraged him to pen some song lyrics. At first Wheeler was hesitant."Obviously you know what imagery is," Payne remembered telling him. "Throw me some images I think I can lead us through the shoals on this."The result of the collaboration is four or five songs, including "Rita Was Her Name," about his first wife, Rita Middleton, to whom he was married for a few years in the 1960s. Payne shared these lyrics from the song:"I hear her sometimes like a clarinet in a darkened window/after the bars have closed and the streets are quiet/a clarinet just around the corner, a week after Mardi Gras.""His instinct on how to do this was just perfect," Payne said.If theres a word besides "author" or "storyteller" that comes quickly to peoples tongues when they speak of Wheeler, its "gentleman."For at least the last 15 years, according to his friend David Stanley, Wheeler participated in "Geezer Lunch" a group of men who got together every Wednesday to have lunch and talk."He was my age, an intellectual, smart, and very, very much a gentleman," Stanley said. "I dont think he has any former friends."When he was sick, Wheeler received many notes and letters from old friends who couldnt make it to visit him."From an unassuming man who never thought his books would impact so many people, both the lifetime achievement award and the accolades from contemporaries really cheered him," said longtime friend Joanne Gardner Lowell.A week before he died, Wheeler received a note from painter and former Livingston resident Russell Chatham."Ive followed your writing for many years, four decades at least," Chatham writes, "and nothing has ever moved me to change my opinion you are the finest author who ever lived and worked in Montana."Wheeler has left his estate to the American Prairie Reserve and an archive of his work to the University of Oregon in Eugene. Elk River Books in Livingston will take over management of his body of published work.On Feb. 17, Wheeler made a simple Facebook post detailing his last wishes: "I prefer a quiet, warm Elks Club wake among friends. No visitation. I am agnostic. No service. Bury my ashes beside Sue."A celebration of Wheelers life will be held from 4:30 to 6:30 p.m. on Thursday, Feb. 28 at the Livingston Elks Lodge.

To order memorial trees in memory of Richard Shaw Wheeler, please visit our tree store.

Photo Gallery

Guestbook

Visits: 95

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the

Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Service map data © OpenStreetMap contributors